8-minute read

Quick summary: Cultural intelligence increases the overall psychological well-being of employees and allows multicultural teams to increase performance by up to 300 percent.

It has been well documented that today’s globalized, interconnected world requires skills for navigating endless new challenges, especially in the areas of diversity and business agility. While these challenges can feel overwhelming, one of the more influential “soft skills” can help us address them: cultural intelligence (CQ).

Organizations that embody a robust view of CQ can increase employee vigor, dedication and team performance—and transform conflicting opinions into valuable resources. But these outcomes aren’t simply added bonuses. When organizations lack sufficient CQ, serious implications can arise. Employee burnout, cynicism, and exhaustion increase, Agile methods don’t work, and multicultural teams’ performance lags. This article will give you a robust view of cultural intelligence, an awareness of the blockers that can hinder its development, and steps for improving your own CQ.

A quick note: Due to the sensitive nature of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) practices, this article is not intended to be a “how-to” for those types of job resources. I’ll be talking about personal development of cultural intelligence. DE&I is essential to the fabric of every organization; however, without expert guidance, these initiatives can lead to staff frustration, harm, and turnover and can also cause a doubling-down on resistance to change. Cultural intelligence is not the solution to all societal and systemic issues, but within an organization, it’s a start for moving towards equitable outcomes and co-creating the inclusive environments that are necessary for diversity initiatives to stick.

What is cultural intelligence, and why does it matter?

Researcher Taewon Moon defines cultural intelligence as “the capability to function effectively in culturally diverse environments.” Although the term is cultural intelligence, Moon’s definition is action-oriented. Some examples of these actions are sharing and implementing different approaches, de-centering value systems that don’t include everyone, and fostering environments for people to do their best work and be their best selves.

The ability to function cross-culturally pertains to everybody. Even if one team or person sits outside the majority culture or “in-group” within a workplace, CQ is needed. Without it, environments often struggle with issues such as difficulties in communication, misunderstandings, and lack of trust. With it, positive outcomes arise both for individual employees and for the organization (e.g. psychological well-being, more effective execution of Agile methods, and improved team performance by up to 300 percent). As companies become more diverse, they will reach a crossroads where they either outperform their previous results or remain worse off.

The landscape: today and tomorrow

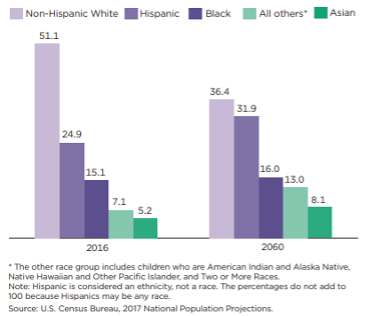

While CQ is already an essential skill, it will likely become a necessity in the future as the U.S. population continues to increase in racial and ethnic diversity. The U.S. Census Bureau projects a fundamental shift in the composition of the under-18 demographic by the year 2060:

(Click image for a larger version)

Regardless of whether this projection holds, CQ remains a need. It’s also worth noting that overall sentiments towards diversity are positive. A Pew study found 57 percent of Americans in the United States say diversity is “very good,” 20 percent say it’s “good,” and 17 percent are indifferent.

But here is a turning point: if 77 percent of the population has a positive view of diversity, why is there a large need for DE&I programs? Roughly 83 percent of organizations took action on DE&I initiatives in 2021. There appears to be a gap between the stated value of diversity and the desired outcomes pertaining to it. CQ can play a part in closing that gap (e.g., by improving psychological well-being, Agile practices, and team performance), but first it would be helpful to identify a couple of common blockers: a narrow view of CQ and the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Common blockers to cultural intelligence

Blocker #1: A narrow view of cultural intelligence

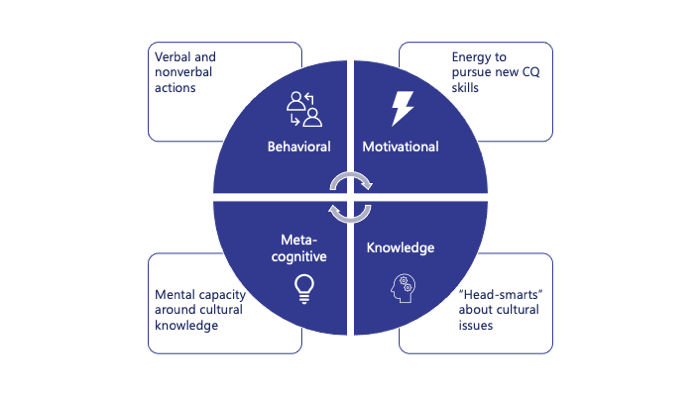

As mentioned, CQ is the capability to function effectively in culturally diverse environments. To explain how CQ is more than simply head-knowledge or comprehension, Moon divided it into four areas:

• Behavioral: Capability to display adequate verbal and nonverbal actions in cross-cultural scenarios

• Motivational: Capability to drive energy and motivation toward learning and developing intercultural skills

• Knowledge (Cognitive): Declarative knowledge about culture, which reflects the knowledge of content

• Meta-cognitive: Mental capability to acquire, be aware of, comprehend, and monitor cultural knowledge

These areas all reinforce each other for growth, which is why we can’t adopt a narrow view of CQ that neglects any one or more aspects.

From my experience, people tend to put more focus on either the behavioral or the knowledge aspects of CQ. A behavioral focus might be expressed with statements such as “I treat everyone the same.” While well-intended, this affirmation, if it excludes the knowledge aspects of CQ, runs the risk of disregarding different life experiences while centering on the perspective of the person saying it. We can’t negate the current and historical context of ourselves and others, because it affects how we see, think about, and interact with each other. By working on our own cultural intelligence, we can become mindful of which actions and inactions might be offensive to another, regardless of intentions. Outcomes beat intentions every day of the week.

A knowledge-based focus can be expressed through using inclusive language, understanding cultural norms, and conveying knowledge of organizational inequities based on ability, class, gender, place of origin, race, sexuality, etc. (such as preferential treatment and gaps in pay and opportunities). But if knowledge were the full view of CQ, it would allow one to negate the behavioral and self-reflective side of functioning effectively in culturally diverse environments.

Even with the best of intentions, when statements and words aren’t paired with change in the person and in the environment, the result is knowledge without recognition of how one may be contributing to organizational harm. It also allows one to finish the goal, earn a certificate, add a badge to the resumé, and call it a day … and therein lies the gap. This disconnect becomes even more problematic when people think they are doing the right thing, but don’t realize they are actually doing more harm. This lack of self-reflection (meta-cognitive CQ) can be bolstered by a second CQ blocker: a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Blocker #2: The Dunning-Kruger effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a psychological occurrence in which someone lacks the capability to objectively measure their own ability or cognition. In other words, the person lacks skill but thinks they have it. This can happen when someone learns about a topic, such as discrimination in a hiring process, and then equates the knowledge of that issue with the requisite skill to bring about change and positive outcomes.

Relating this phenomenon to CQ, if we play into the Dunning-Kruger effect by thinking we have the skills, but lack the ability, the result will be organizational harm. A good way to combat this gap is by adopting an attitude of humility and teachability, assuming we always have room for growth. I also think that those who are truly experts “know what they don’t know,” so to speak.

How to build cultural intelligence

When taking steps towards change, people typically avoid actions and decisions that create regret and seek those that cause pride. This includes avoiding psychological pain by disregarding, refuting, or minimizing any feedback or information that conflicts with a positive self-image.

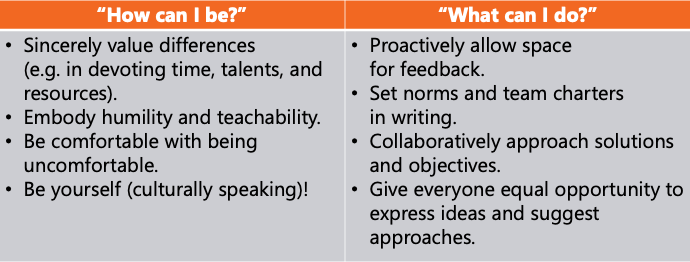

While teaching CQ, I’ve seen a tendency for people to say “All right! What can I do?” almost as a way to jump to the finish line and avoid the struggle. While that question is important, it needs to be considered in tandem with “How can I be?” which focuses on the necessary core behaviors and attitudes to function effectively in culturally diverse environments.

Ways to develop CQ outside of the workplace

• Place yourself in cross-cultural settings (ideally through invitation, not consumption).

• Identify your own culture (e.g., deep-seated norms, expectations, what is considered offensive).

• Learn from local leaders who are giving visibility to different people and communities.

• Find answers to questions through a variety of resources (e.g., professional voices in the CQ space, online search results, someone who has agreed to be a resource).

• Read and learn about different cultural norms, national cultures and subcultures, and current and historical leaders.

I’ll say it one more time: cultural intelligence is the capability to function effectively in culturally diverse environments. For everyone to do that, collective, actionable change in cultures, processes, and physical spaces is essential. By embodying humility and teachability—and leaning in when things don’t make sense—individuals with CQ skills can play a part in that process.

Again, CQ is more than learning to “be nice to people,” reading a book, sharing a post, or claiming allyship. It means we struggle with each other when things are inequitable, but also celebrate together when there are wins. While psychological well-being, success in Agile practices, and team performance are direct benefits, cultural intelligence is ultimately about everyone thriving together—and that’s the secret sauce.

Like what you see?

Nick Ravi-Johnson is a consultant in Logic20/20’s Strategy and Operations practice and holds an M.A. in industrial and organizational psychology.